Decision-Making is hard at Mozilla. We often face inertia and ambiguity regarding who owns a decision. It can feel as if many people can say “no” and it’s hard to figure out who can and will say “yes.” Our focus on individuals as empowered leaders can make it hard to understand how to make a decision that is accepted as legitimate. This impacts everything from deciding what platforms or tools to use, saying yes or no to projects, to the role of volunteers and supporters in our work. I hear that decision-making at Mozilla is hard regularly, and I’ve experienced it myself.

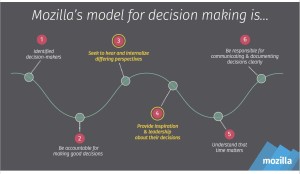

A few months back I decided to get involved directly. I decided to develop case studies of how to make decisions well, using the decision-making model I presented during Mozilla’s Portland gathering as a guide. The slide is below.

If you’d like to spend 20 minutes or so listening to this part of the presentation go to minute 1:35 here.

I started by recruiting Jane to do the project management and make this a more consistent project than I would do on my own. The next step was asking a few people if they have decisions they are struggling to get made and if they would be interested in piloting this plan with me. I started with people who know me well enough to be comfortable with give-and-take. In other words, a few people who aren’t so intimidated by my role and can tell me things I don’t really want to hear :-). I’ll widen the circle over time. There is also a set of people I think of as “standing members.” This latter group currently includes:

— Jane Finette, for project design and management;

— George Roter, for his participation focus;

— Larissa Shapiro, to help build inclusion of diverse voices into our decision-making; and

— me.

We’ve learned a few things already, even though we’re not far enough to have a case study yet. Here’s what we’ve learned so far.

- The decision-making model is missing at least one key element. It’s so key that we currently call it “Item 0.” (We’ll probably rename it item 1 at some point.) This is — identify the actual decision that needs to be made. This sounds obvious. But the actual decision may be very different than the question as first presented. For example, in one case the initial question was something like “what’s the most cost effective way to do X?” But in reality the decision turns out to be things like “How important is this product feature?”

- We need a shared understanding of what “community” means and how we think about our volunteers and community when we make decisions. We need a way of doing this that respects the work being done and that simultaneously allows us to decide that not every activity should be supported forever. George Roter is our point person for this.

- We decided to create something I dubbed the “Map of the Land Mines.” This will start as a list of questions that tend to stop forward momentum and leave us paralyzed. Our starting list here is:

— How public should we be? When is open appropriate / when is it not?

— Are we collecting data?

— Is it important we choose open source for our tools?

— How do we think about supporters and volunteers?

Of course we’ll want more than a list. We’ll want tools for how to approach these topics so we can all get unstuck and stay unstuck.

We’ll meet every 2 weeks or so. Steps 3, 4 and 6 of the decision-making model are about communication, participation and documentation. So expect to hear more, both about the process and the decisions areas we’re using to build case studies.

Comments and suggestions are welcome, either here or via other channels.